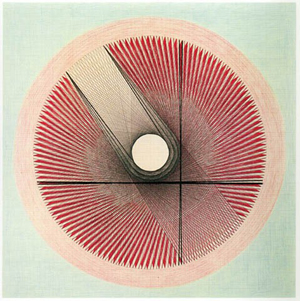

I followed a certain line. A line not of words, but an image and dangerous, which is to say approaching perfection. I followed that line and before I knew it I was in the end-room.

The end-room is a veritable paradise machine.

The healed stump of every fragmentary line and the raw end of every terminal one are in the end-room wound on spools and unspooling.

All lines—even those made of words—lead to the end-room so that in this detail the end-room resembles a pin-cushion or a tree struck by lightning. Lines not only enter it, they exit it too, so maybe it is more like my house on fire or a ball of yarn martyred by knitting needles.

But really, what is the point?

The point. It doesn’t exist in the world.

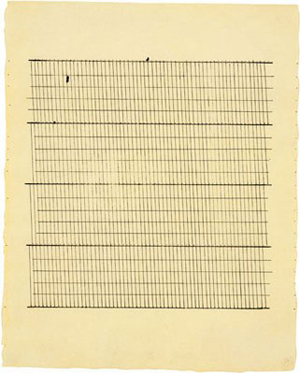

Agnes Martin, the painter of lines and grids, said that. She also said:

people see a color that’s not there

These two taken together form as good a definition as any of any art, and are sufficient reason to follow the line known by its color which is not there, and its point, of which there is none and as real as this rock I found with my sister in the village of La Pointe on Madeleine Island in Lake Superior.

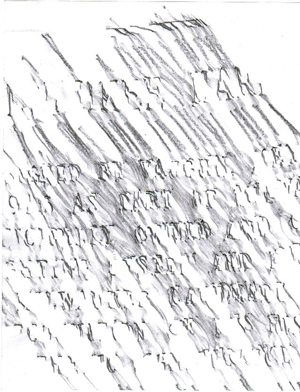

Yes, the line is very real even if the point is not, and we have the earth itself to thank for the line and its mineral origin in rubble laid down in strata, in stutters, just as we have the brain to thank for the point that doesn’t exist and for colors that are not there but are felt all the same—a line of reasoning offered by my friend David-Baptiste Chirot, whose work brings everything back to the line.

If these are the geometries of the end-room, how can I not be an optimist? Here there is every utterance in every material that ever ended—or never will—with a flourish, with a full-stop, with a point, or none at all, including telegraph lines that throw off dots and dashes both.

.– …. .- …. .- – …. –. — -.. .– .-.

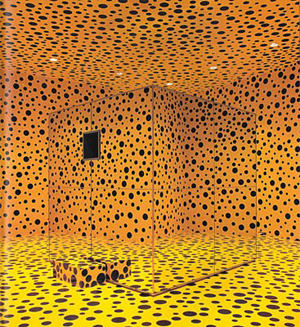

END-ROOM COVERED FLOOR TO CEILING WITH DOTS STOP HERE IT IS STOP HOPE LINES NOT TOO DISTRACTING OR DOTS TOO FIZZY AS THEY POP STOP REGARDS KUSAMA YAYOI

The line is abstinent, the dot is prodigal. You may think the opposite, and still one day they will meet, trailing decimal places through the sand and salt-roses.

If a line can be a sentence, a sentence is period of time. When a period refers to a specific kind of sentence, it is an adventure that seeks to explode time. Clause after clause, the periodic sentence comes to its senses only at the end. In this it mimics the natural life of a human being.

All sentences are lines but not all lines are sentences. I’m not sure about that. Yes. Not all sentences are lines but they taper like knives so that there are barb wire perimeters and butterfly feelers. There are smoke- foam- and freeze-lines. Some lines are branches that are limbs—a full-stop the pretty nest in their crux. There are full-stops shaped like buttons shaped like bullets.

But is there really such a thing as a perfect line? Or a perfect broken line?

Agnes Martin thought she could draw a perfect line if her mind were clear. For the time being, however, there can be no clarity. This line of thought comes to a point that pierces the end-room and the end-room bleeds a bloody rain. Better to stop here than to keep poking at perfection.

I still have a city to cover with lines—d. a. levy died young and there are days when his ghost teaches clothing and other days when it teaches nakedness. But what about the city’s own lines, the city screaming to be uncovered?

A scream is a line that goes straight to the heart of the end-room.

It should be clear now, that from within the end-room good-bye is gradually misunderstood. Good-bye is a transparent swindle mirrored endlessly in the end-room. There is no good-bye—what would be the point of it?

These lines run whole, and whirling out: come in broken, and dragging slow.

In “The Log and the Line” chapter in Moby Dick, Melville was referring to harpoon lines.

Melville’s end-room not only looks like a whale, it may in fact even be a whale, and white. The strips of whale blubber that were cut into “Bible leaves”—they opened like a book and were rendered meaningful by fire.

To one who reads, everything is a book, and the end-room, whether it is a whale or not, is a book of another dimensional realm so that it is perfectly possible to read the end-room. But it is impossible to read in it. In it, one cares not at all for reading anything but the end-room. Jonah knew this.

Strange to say, there are individuals who although they may inhabit it do not see solid night. These same individuals can follow a line to the end-room and see what is truly not solid, not like night at all and densely peopled, but a broken light bulb, in pieces and scintillating like the soul.

Self-obliteration by dots. This is what Yayoi Kusama calls her “dots obsession.” Yes, without a doubt her self disappears in the end-room, the dots absorb her light, ending her sentence in a pop and tintinnabulous.

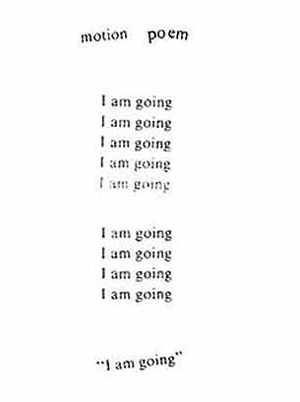

The dress I was wearing. No, the dress and candy cigarette. This is what is called “progress in self-delineation” and it bears a familial resemblance to the line that poems cut out of poets.

Je n’avais pas emporté la ligne étroite de mon retour.

René Char! If he couldn’t take with him the thin line of his own return, how can I?

But in as much as every poet, verbal or otherwise, is the ready assistant of a knife-thrower, I will continue to perform this trick and follow the line, however visible, to the end-room, however invisible.